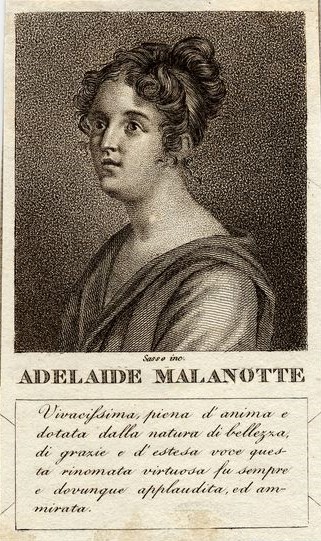

Adelaide Malanotte

The passionate and nonconformist diva

Giovanni Antonio Sasso (1809-1816), Adelaide Malanotte, print - International Museum and Library of Music, Bologna

The Roman amphitheater is a worldwide symbol of opera. The festival, held every summer in the largest open-air opera house, began in 1913 with the first performance of Giuseppe Verdi's Aida, but as early as the eighteenth century, opera performances were held regularly in Verona that, albeit with difficulty, featured women. By the customs of the time performing in public, in front of an audience of strangers, was morally inappropriate. Singers were considered women of easy virtue and unfortunately were often chosen by impresarios more for their aesthetic appearance than for their vocal talent.

A reversal was due to the decrease in the number of emasculated singers (castration was banned), which provided opportunities for women to fill empty spaces particularly in the contralto role. Prominent among them was Adelaide Malanotte from Verona. Born in 1785, Adelaide was the daughter of a wealthy merchant and began studying music for pleasure at an early age, but at the age of 21 she decided to become a professional singer in order to cope with the financial disruption that had affected her family. Adelaide immediately enjoyed great success and began singing in other cities as well. Among her admirers were Napoleon's brother Lucien Bonaparte and the poet Ugo Foscolo, who praised her art and beauty. Composer Gioacchino Rossini wanted her in the part of Tancredi, adapting a male role to the Veronese singer's soft contralto voice and rewriting an aria especially for her. After her successful debut, she became a diva of Rossini's operas, applauded in major Italian theaters.

An emancipated and out-of-the-box woman, despite being married she became romantically linked to the poet Luigi Lechi, who would remain her companion for life. It is an "uncomfortable" love since Lechi was controlled by the Austrian rulers because of his patriotic and subversive ideas. As if this were not enough to draw criticism from the well-wishers, Adelaide's husband and their children also came to live in the lovers' home on Lake Garda. She prematurely retired from the stage due to health problems.

In 1823 the diva tried unsuccessfully, to throw off the police in order to avoid the arrest of her companion: a momentum that defines the portrait of a passionate woman who lived totally outside the conventions of her time.